This is Part 2. (Link to Part 1)

An engineered system is purpose-built to fit its environment and achieve certain objectives while meeting some constraints. Well-engineered systems are utilitarian, routine, boring. They make it easy for people to do their jobs, letting the system fulfill its purpose without causing harm.

The biggest difference between engineers and other technical people is that engineers are responsible for an entire system through its whole lifecycle: not just its construction and acquisition, but also its utilization, support and retirement. Using science and logic, they build a system that they can prove is trustworthy. It's not a perfect method, but over the years, the method has evolved to become pretty good.

The root cause of the disaster is clear: a profit-seeking American company, Union Carbide, owned 51 percent of a pesticide plant operator in a poor country. The plant was unprofitable, so Carbide drastically cut its operating budget to save money. After the failure, the government failed to hold the company accountable. Even when it won a small sum as compensation in court, it failed to ensure that the funds reached the victims.

But even given the poor business decisions, the plant need not have blown up. When you analyze the Bhopal tragedy down to its engineering essence, you find a lack of systems thinking.

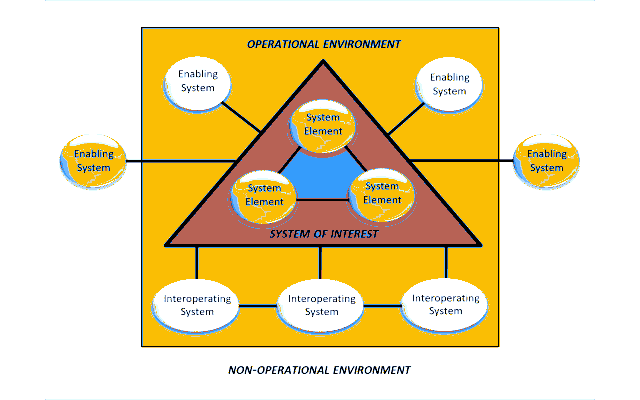

An engineering system, such as a chemical plant, provides capabilities that its constituent parts cannot provide on their own. You cannot think only of the constituent parts---the chemical processes, management, shareholders, employees, and so on, but of the system as a whole.

Such a system must be considered together with other systems that it interacts with, to make sure that it can provide these capabilities while protecting the interests of all of its stakeholders.

The plant does not work as a system unless all the stakeholders' interests are protected. A critical stakeholder is the community living close to the plant, and important "interoperating systems" are the medical and transportation support systems of this community.

When the plant was set up, key engineering agreements should have been made between the operator, Union Carbide India Limited, and the government. I don't know whether these were written down or not, or whether they were simply not enforced, but the following three facts are important:

The government allowed the plant to be sited too close to densely populated areas, and it did not provide information to the local communities and hospitals about the hazard and its mitigation.

The plant operator, Union Carbide India Limited, went along with corporate cost-cutting. It removed critical maintenance and safety measures well past the point of danger and continued operating, never raising the alarm.

After the site was abandoned by the operator, the state government allowed hundreds of tons of toxic waste to seep into the groundwater and harm more victims.

The above three actions should never have been allowed to happen, purely on engineering principles alone.

In Action 1, the government's job is not only to sign zoning permits, but also to make sure that citizens as stakeholders, and the hospital as an interacting system, get the information they need in a usable way.

In Action 2, the operator's job is not only to reduce costs, but to preserve safety, a critical capability.

In Action 3, during retirement, the government's job is to hold the operator accountable for cleanup.

The disaster could have been prevented by following basic system engineering principles. For example, here are two principles:

The principle of Commensurate Protection means that any element whose failure would cause very bad things to happen, must be protected most effectively.

The principle of Defense in Depth means that, to avoid single points of failure, you should use multiple protective mechanisms along different failure sequences.

There are thirty such principles listed in a publication from the National Insitute of Standards and Technology (NIST) on engineering trustworthy secure systems, NIST SP 800-160, published in 2018. These principles let you reason about a system that you want to make trustworthy.

To actually use these principles you need judgement and experience, but it is possible. Real systems are built successfully every day.

The makers of The Railway Men wisely focused on story and drama. The show follows the few heroes who saved the day.

Heroes are extraordinary protagonists who know what to do when things fail. In a crisis, people instinctively follow them. In the show, a panicked mob angrily surrounds the stationmaster and makes demands. A police constable pulls a gun on them and says in idiomatic Hindi, "Back off and just follow what this man says! In this land of the blind, he's the only light."

It's a memorable line. We like stories about heroes. Their lives are cinematic, full of drama.

But the purpose of system design is to avoid the need for crises, heroics, and drama. I can't help thinking that proactive engineering in Bhopal might have been able to save many more lives.