This is a more personal post than the usual. My father passed away this week in India.

My brother and I were remembering the many ways in which he touched our lives, as he had doubtless affected so many others.

Baba was an old-school father, in an era when fathers didn't spend much time with their children. But when he did, he liked to show us a magic trick like cutting off his own finger, or a mathematical puzzle. He showed me how to use his slide rule, a Faber-Castell Aristo with beautiful red and green markings in a leather case.

Very rarely, we talked about important things.

He wouldn't hurt a fly, literally. If he caught a creature inside the house, he would carefully open the window and toss it out. Even when a cobra came out of the grass in the monsoons, he would not let us hurt it. Raised in a strict Maharashtrian Brahmin household and then in the College of Engineering in Pune, he was well-read but hadn't seen much of the real world before entering the Indian Military Academy in Dehradun. In the officers' mess they had arranged yellow flowers on the tables for the cadets to eat, which he discovered were boiled cut eggs.

I had always wondered how a peace-loving, creative and bright mind like his had found itself in a rigid, top-down military bureaucracy. After getting his engineering degree, what had possessed him to become a commissioned officer?

I did ask him once. He said he had been bored working for a public works department in a town in Gujarat and for the state-owned oil company ONGC. Besides, he said, one of his childhood buddies from New English School in Satara had entered the National Defence Academy and loved being an army officer. So, he decided to sign up, too.

I wanted to know how it had turned out for him.

Like many regiments in the Indian army, the Bombay Engineering Group, a.k.a. the Bombay Sappers, is much older than the country, having been raised even before the British Indian army, in the days of the East India Company. These are combat engineers whose business is mines, bridges, and similar technical work.

From his home base in the Bombay Sappers, Baba was often sent to faraway places. His postings read like a travelogue of the Indian subcontinent, a lot of it in the Eastern and Western Himalayas: Nagaland, Tezpur, Shillong, Mussoorie. He was often an instructor for project management or technical subjects at some institute or another.

However, his official obituary from the Bombay Sappers has a few gaps during classified assignments. One of these gaps is for a few months starting in November 1971, the period of combat operations in the Bangladesh Liberation War.

I had to dig a bit to find out what he did during the war.

Indian troops invaded East Pakistan to help the Bengali rebels, forced the Pakistan military to surrender, and created the new nation of Bangladesh. If ever a war was justified, it was the Bangladesh war.

Embedded within the invading Indian army brigades were engineering units. The engineers "shape the terrain" in battle. They plant or clear mines and lay down or demolish road surfaces or bridges, enabling their own side to make progress while hindering the enemy.

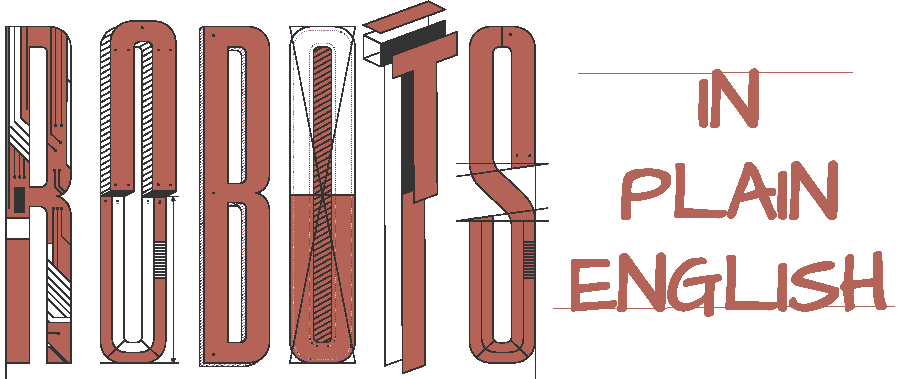

East Pakistan was criss-crossed with rivers in loamy and marshy soil. It was difficult to move equipment and material. Many roads, bridges, and ferries had to be built and destroyed around the clock, often under enemy fire. Military historians called it an engineers' war.

Baba was a Major then in the 268 Engineer Regiment, and he mentioned to me one particular bridge across the Kabadak river that had been destroyed by the retreating Pakistani troops. I was able to find a contemporary picture of it:

The 268 Engineers had to rebuild the bridge temporarily using prefabricated parts carried into battle.

I got a picture of the rebuilt bridge from Baba's comrade-in-arms, Major SS Rajan. The broken sections of the original bridge lie undisturbed below.

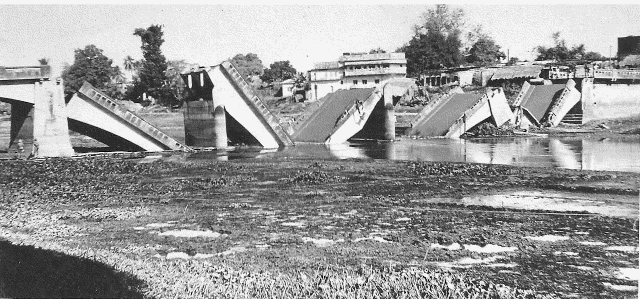

The new bridge is a simple, continuous type of "Bailey bridge" that spans the river from end to end, but this river was too wide, and the engineers had to support it in the middle by building a pier made of steel cages.

My father designed a "distribution beam girder," a rigid structure made of steel plates, to distribute the load on to the new pier. He got it made from a shipbuilding yard in Calcutta. They produced it overnight, and the army transported it and assembled it on site.

Maj Rajan, the commander of the company that built the bridge, also gave me the picture below.

You can see Maj Rajan directing the bridge placement on top of the new steel structure. Supported in this way, the bridge could span the river successfully.

The war was over fourteen days after it was declared, a complete and rapid victory.

Maj Rajan, who retired as a Colonel, told me this week that my father had designed the entire custom structure by himself and that it had worked the first time. "He was a brilliant man," he said.

I am sure it must have been a great feeling to have been useful, to have served your country and to have done it well.